The Zoologisk Museum is part of København University and the National History Museum of Denmark. Currently, they are getting ready to move by October 2022 to a new location being built in the Kings Garden.

-Females typically weigh 200-350 kg, males 400-600 kg, largest male on record weighed 1002 kg

-Largest bears measure 3 meters in total length

-Females reach sexual maturity at 4-5 years, males at 5-6 years,

-Litter size 1-4 cubs, most often 2.

-Polar bears are uniquely adapted to the extreme conditions of life in the High Arctic and live most of their lives out on the Arctic sea ice.

-In cold Arctic climates, energy is in high demand. Fat is the predominant energy source and the polar bear has a fat-rich diet throughout life. The polar bear’s main prey is ringed seals but also hunts other seals, and eats whale carrion. Polar bears have substantial adipose deposits under the skin and around organs, which can comprise up to 50% of the body weight of an individual

-Global population estimated at around 26,000 individuals, although this estimate is associated with a great dear of uncertainty.

BESIDES CLIMATE CHANGE

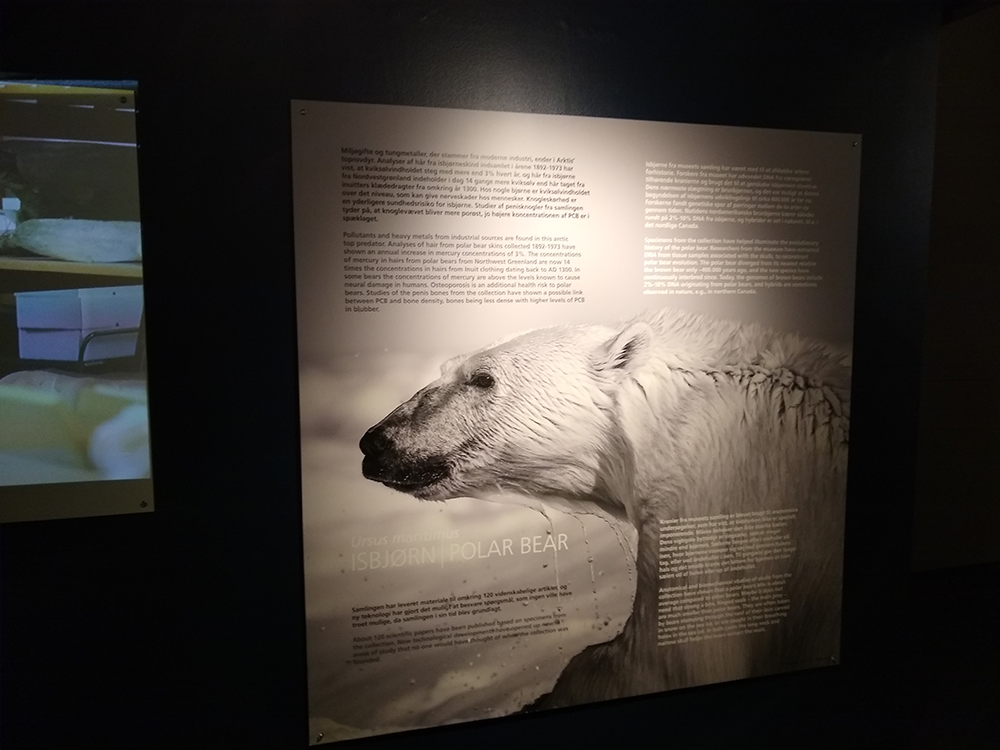

Pollutants and heavy metals from industrial sources are found in this arctic top predator. Analyses of hair from polar bear skins collected 1852 – 1973 have shown an annual increase in mercury concentrations of 3%. The concentrations of mercury in hairs from polar bears from Northwest Greenland are no 14 times the concentrations in hairs from Inuit clothing dating back to AD 1300. In some bears the concentrations of mercury are above the levels known to cause neural damage in humans. Osteoporosis is an additional health risk to polar bears. Studies of penis bones from the collection have shown a possible link between PCB and bone density, bones being less dense with higher levels of PCB in blubber.

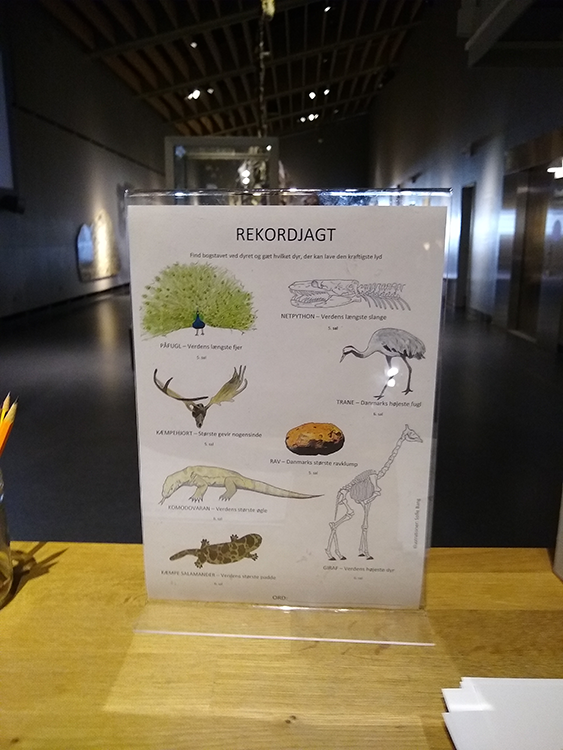

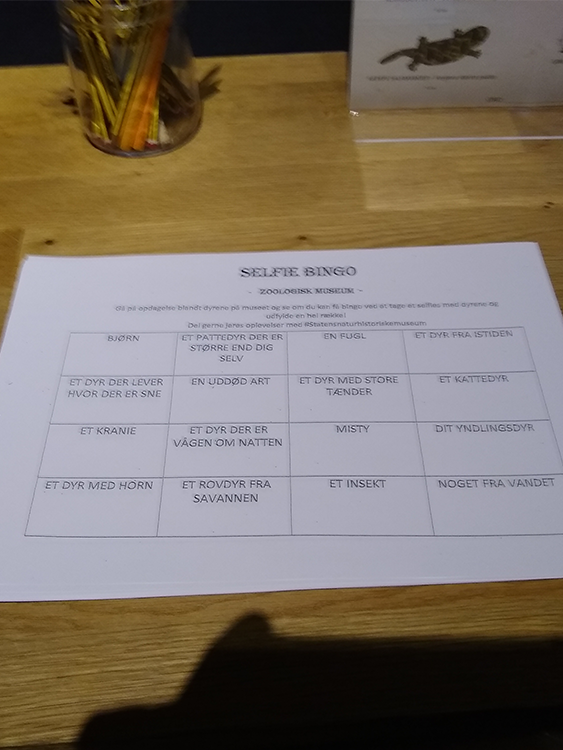

Always something for the kids

Precious Things

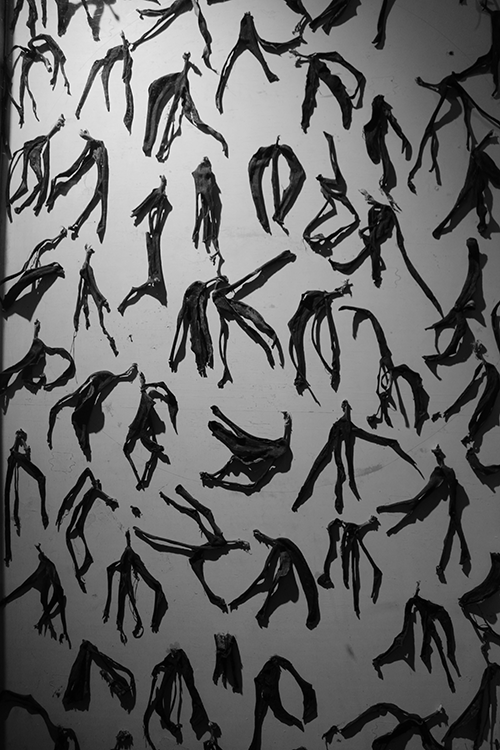

The move led to an exhibit called Precious Things. As they prepare to pack up they are going through everything they have. They have numbers of treasures in storage.

The museum’s treasure trove

has amassed all sorts of wonderous objects

over the past 400 years.

The way we perceive nature around us

has changed over centuries and decades,

and so have our ideas about what precious implies.

However, it is still with wonder and enchantment

that we collect rocks, animals and plants. To study them

and wrest from them their innermost secrets

– or just to admire their beauty.

People collect all sorts of things: stamps, airplanes, butterflies… Most collections eventually perish, but some are bequeathed to museums, endowing them with eternal life. This is how a collection of snail shells ended up in the Zoological Museum in 1905. The collection consists of snails gathered in different parts of Denmark, and represents almost all the species found in the country. The accompanying notes detail where and when the specimens were found, alongside those of the collector: Hans Christian Andersen.

NAUTILUSES FROM THE ROYAL CHAMBER OF CURIOSITIES

At first glance it is far from obvious that these find goblets from the Royal Danish Chamber of Curiosities are made of squids.

The nautilus is a squid-like creature with an outer shell measuring 3-30 cm in diameter wit up to 90 tentacles without suction pads. They live at a depth of 150-300 m, where they scour steep cliffs for crustaceans, fish, mollusks and other bottom dwellers. Nautiluses are active at night, but during the day they sink to the seabed, where they rest with their body retracted into the shell, protected by the very thick skin on the head forming a kind of lid.

These goblets made of carved nautilus shells became part of the museum’s collection after Frederik III’s Royal Chamber of Curiosities was dissolved in 1825.

THE KONGSBERG SILVER

It is said that a boy and a girl herding animals on the pasture were the first to find silver at Kongsberg, Norway, in 1623. They came across the silver because an ox stuck its horns into the ground, exposing the shiny metal. When they took it home, their fathers melted it down and made silver buttons, which they sold. This activity came to the attention of the authorities and one of the fathers had to reveal where the precious metal came from.

The story may be a legend. However, soon it reached Copenhagen and Christian IV, who immediately commissioned mining in the area. Silver meant money – and money was needed at the Royal Palace in Copenhagen. Not only did Kongsberg have silver in large quantities, but some of it was exceptionally pure and did note even need to be extracted from ore.

The massive thread of silver, one of the museum’s finest treasures, comes from Christian VII’s chamber of curiosities. Presented to him in

1769, it was described as follows: “A magnificent thread of joined-together solid sterling silver stems or branches, depicting, when the thread is standing upright on its widest part. a capital Roman C, as the initial letter of your most gracious majesty King Christians VII’s name and as if covered with a crown.

FLORA DANICA

Every plant in the kingdom – nothing more, nothing less – what the ambitious plan for ‘Flora Danica’. King Frederic V commissioned this great pictorial masterpiece, and the German doctor and botanist, Georg Christian Oeder, initiated the production of it in 1761.

One of the ideas behind ‘Flora Danica’ was that knowledge of plants was essential for economic growth, and in the spirit of the Enlightenment it seemed obvious that knowledge should not be reserved for scholars. The work was to be spread around the country and used by bishops, priests and others who were in contact with ordinary people.

The first set of 60 species was published in 1761. ‘Flora Danica’ kept various illustrators, engravers, botanists and publishers busy for more than 122 years. A total of 3,240 copper plates were engraved and used for printing. The vast majority are of plants, but there are also fungi, algae and lichens.

The herbarium specimen, copper plate, and the board shows ‘Pedicularis sceptrum-carolinum’.

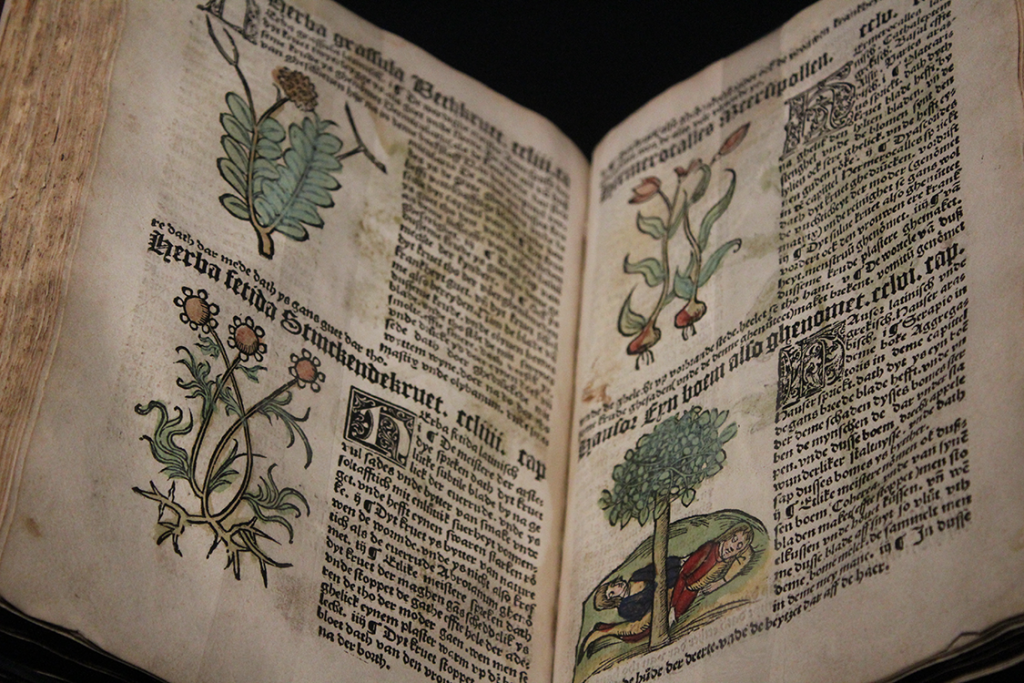

HORTULUS SANITATIS

‘Hortulus Sanitatis’ (The Garden of Health), published in Lubeck in 1520, was one of the most popular and influential herbal and medical books of its era. Combining knowledge from ancient classical writings with biblical and popular myths, it lists the plants, animals and minerals of the known world.

It mentions the mandrake, a plant that screams when it is dug up-a sound that kills anyone who hears it. And the bausor tree, which has a poisonous scent that lays waste to everything for miles around it. Not to mention unicorns, basilisks, mermaids and mermen, and al sorts of other weird and wonderful creatures.

However, it also describes real plants and animals, and provides specific instructions on their medicinal use and treatments for everything from bad breath, nosebleeds and snake bites to tumours, concussion and broken limbs.

The book teeters on the verge between the practice of uncritically copying classical writings prevalent in the Middle Ages, and the era of more empirical and practical science heralded by the Renaissance

NEPTUNES CUP

In Roman mythology, King Neptune is the god of the sea and it is not to imagine him taking a sip from this cup.

This strange sea sponge lives in relatively calm waters less than 100 m deep. The largest specimens are over a metre tall and estimated to be several hundreds years old. We know virtually nothing about the spread and habitats of the species.

King Neptune’s cup was first described in 1820. At the time, it seems to have been quite common in south east Asia. I was collected in great numbers and exhibited in natural history museums around the world. Four specimens are held in this museum. They are listed as originating from ‘East India’ and ‘Singapore’, and probably entered the collections somewhere between 1820 and 1864

After the 1860s, no new specimens appeared in museums, and for many years, the species was thought to be extinct. It was not seen again until 1990, when a single specimen was fished out of the waters of Australia’s north coast. No more have been found since; however, in 2011, two living specimens were observed for the first time on the seabed off the coast of Singapore.

THE WHALE CHAIR

In 1836, a fin whale ran aground at Agger Tange at the western mouth of the Limfjord. It was a sensation – the first registered stranding in Denmark of a fin whale, which is the second largest whale in the world, only next to the blue whale. The carcass was dismembered, and the skull sent to the Zoological Museum in Copenhagen.

Then, in 2013, Herning Museum sent this chair to the Natural History Museum of Denmark. It is made from parts of the skeleton of the whale stranded in 1836, and is allegedly one of 12 by a man from Asp, near Struer.

The chair was handed in to the Herning Museum sometime in the early 20th century, but the whereabouts of the other 11 chairs remain a mystery.

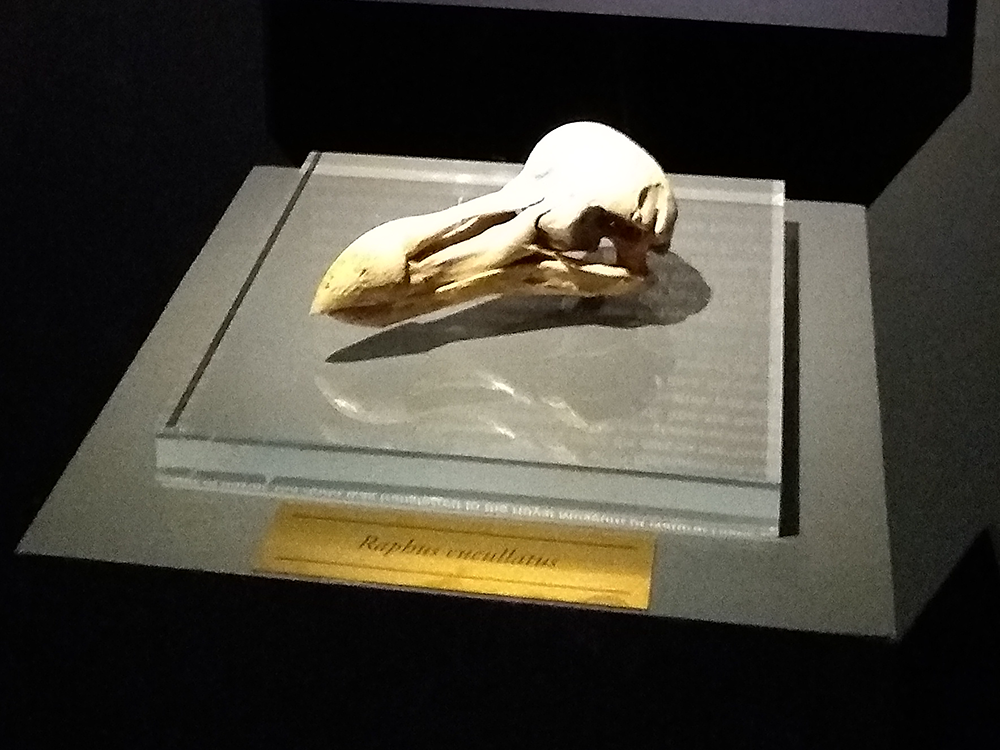

THE DODO SKULL

This skull of the extinct bird, the dodo, is one of the museum’s greatest treasures. The only othe existing specimen in the world is found in Oxford, England.

The dodo was first described in 1601, when Portuguese mariners landed on the island of Mauritius-the only place the species ever lived. They described it a big and clumsy and noted that the meat was not very tasty. Many years later, in 1843, Johannes Theodor Rienhardt from the Royal Museum of Natural History, declared that the lumbering creature was some kind of pigeon. Although met with great skepticism at the time, his view is now acknowledged as being correct. The closes living relative of the dodo is the Nicobar pigeon.

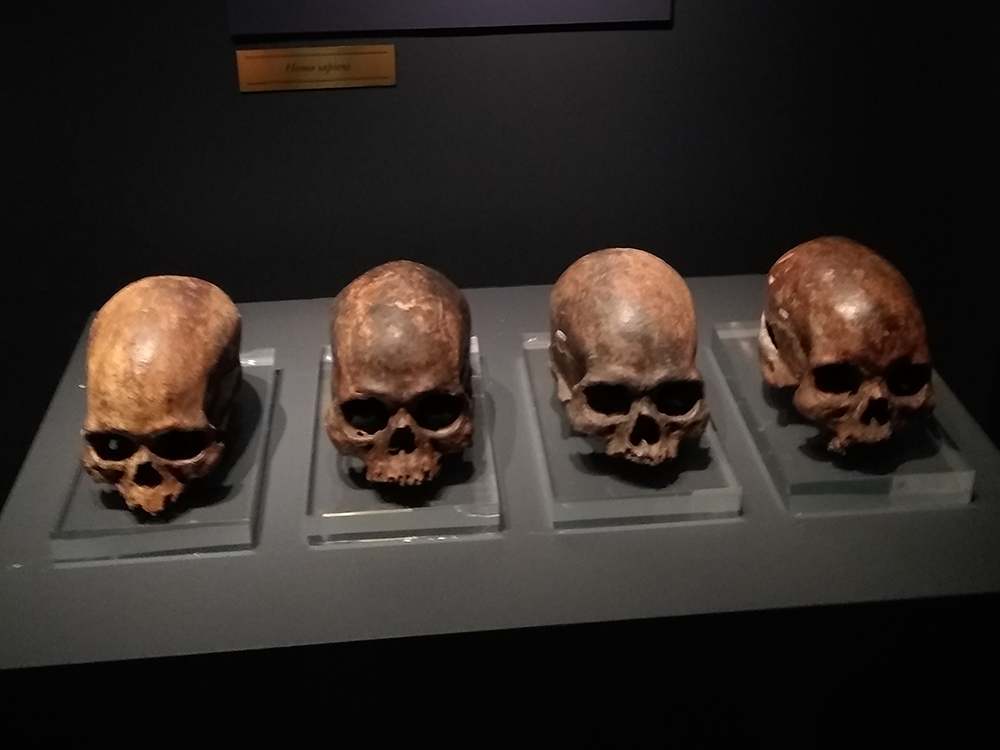

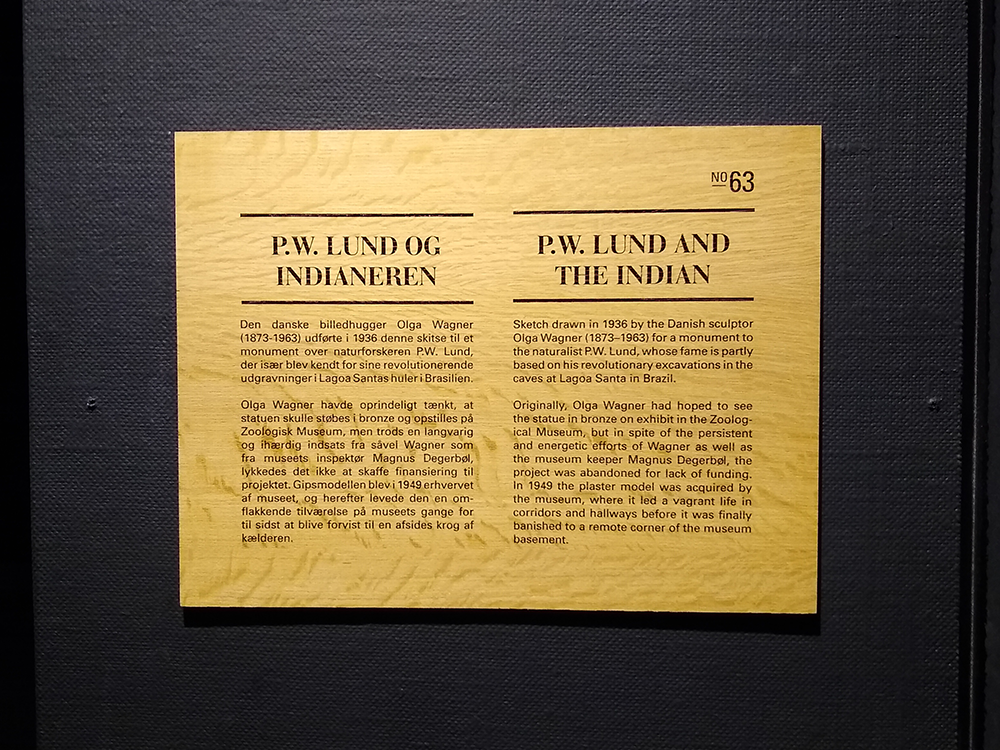

P.W. LUND’S HUMAN SKULLS

In 1833, the Danish zoologist P.W. Lund travelled to Brazil, where he settled in the village of Lagoa Santa. The surround area featured many large caves filled with stalactites, stalagmites and amazing rock formations, which Lund began to explore and excavate. Skeletons of animals that had fall into the caves or were killed in other ways had accumulated there for thousands of years. Many were from extinct species such as the giant sloth, glyptodon and the sabre-toothed tiger.

In 1841, he found human bones. Lund suggested that this strongly indicated that people had lived in America long before the Europeans arrived. and that humans had lived here at the same time as the now extinct animal species. e also believed that the people who had previously lived in South America were the same as the Indians that the Europeans met when they first arrived on the continent.

Lund’s skulls remain of great scientific value. DNA remains have not yet been found in them, but if-or when-that happens, it may help to shed light on a very important chapter in our understanding of how humans spread across the globe. Who were the first people in South America, and where did they come from?

DARWIN’S GIFT

In 1854 The Royal Natural History Museum in Copenhagen received a gift from Charles Darwin: a box of barnacles. Darwin had spent many years describing all sorts of barnacles – a group of crustaceans living on whales backs and other surfaces in the sea.

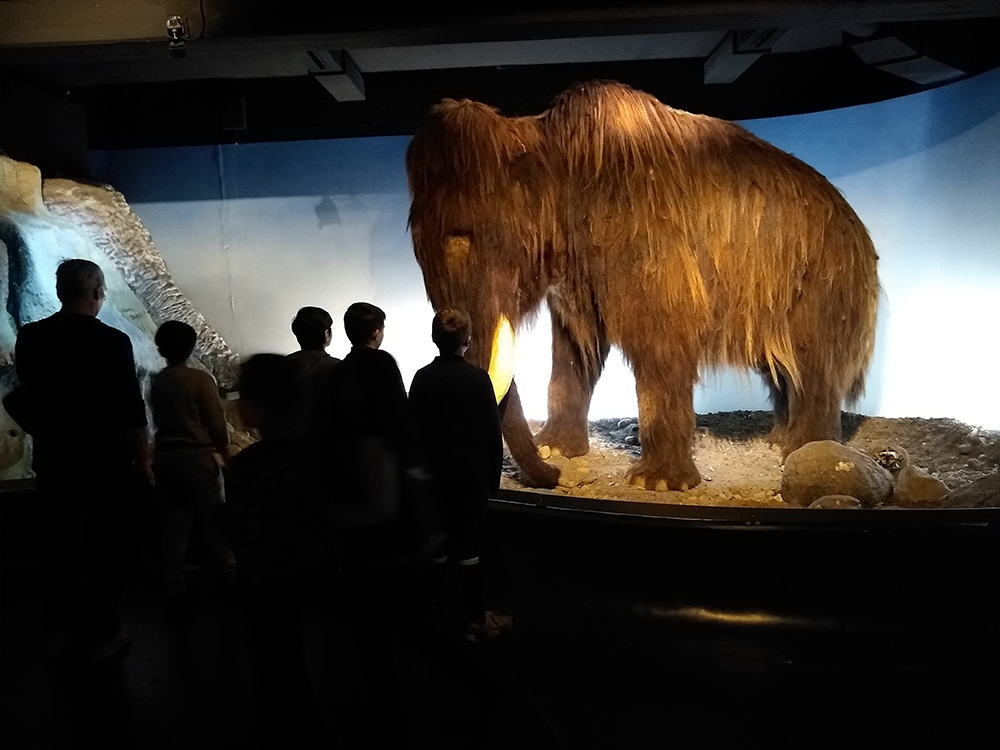

From mammoth steppe to cultural steppe

THE MAMMOTH STEPPE

a summer day somewhere in Denmark 16-17,000 years ago

The ice age is nearly over. The ice sheet has retreated but has left thousands of large and small dead ice blocks scattered in the landscape. Vegetation is sparse and at this point only a few animal species can manage in the area

I personally am intimidated by these really big animals so I observed the mammoth from across the room. We turned the corner and I was standing next to the skeletal tail of a whale. Gulp. I “womaned up” and continued through the museum.

AUROCHS

Complete skeleton of an aurochs bull excavated by Zoological Museum in a bog at Prejlerup near Vig in Odsherred. Together with the skeleton 15 flint microliths were found lying close to the bones of the hind part. The microliths represent arrows shot into the bull. The hunt failed and the bull escaped its pursuers but drowned in Prejlerup lake. The event took place around 7400 BC.

THE BEECH FOREST

-a summer day somewhere in Denmark nowadays.

Thousands of small and larger forests are scattered in the present cultural landscape – altogether 10% of the country is covered by woods. All forests are planted and only 40% of the area is covered with native tree species. The beech dominates the deciduous forest.

John Olsen 2002

We want to come back to see this museum in it’s new home. New exhibits being built look amazing!

Italicized text is from the displays.